Thoughts and Stuff

Do. Read. Write.

Sharing life's lessons here. Telling business stories across the web.

Losing My Childhood

Four years ago, I lost my childhood friend. She was twenty. She wore a wedding dress to her funeral; a poignant reminder of one of her cherished dreams. I don’t remember what I wore on the night that I was told we had lost her. I don’t remember the day itself; what I ate, what I was, what I thought before I woke into her absence. I remember falling on my knees and crouching to my ankles. I remember the ache that began gnawing deep inside me, its manifestation in the way I scratched my legs till they bled, a vestigial habit that I would slip into when I did not get what I want, in this case, her healing.

In the days and weeks that followed, I confronted my grief with memory. My childhood friend was an exemplar to me; someone I called a friend but who surpassed me. I wanted to emulate her. Whenever I met her, I would feel that something was amiss within me, that she had figured out something that I was yet to discover. It was never the kind of feeling that paralyzes you into thinking that you are not good enough. It was the kind of comprehension that warms you, that makes you want to be a better version of yourself. “I never knew anyone who loved God like you did,” I wrote. I wanted to love God like she did. So I confronted my loss with an almost manic desire to be like her. “One thing you taught me is to trust God,” I eulogized. I desired to replicate her life, albeit blindly and unsuccessfully. Yes, confronting my loss was a fruitless endeavor. I didn’t become her. I didn’t become the brown beauty who seemed to have mastered the business of loving God. In fact, my attempts at religious devotion only succeeded in holding up a mirror to the grief that was consuming me.

Though I don’t wish for it, grief fascinates me so much so that my only regret in dying will be the inability to describe the loss of my life. Few experiences, I think, give one that depth of inventiveness, that emptiness that words can never fill, but that can only offer a momentary catharsis. I first flirted with grief as my muse when I read I Dreamed of Africa, the story of Kuki Gallmann’s life and loss from the early 70s when she first moved to Kenya. In the middle of the book, you mourn with her as she loses her husband to a road crash and her only son to a snakebite. When I lost my friend, the stories of Joan Didion and Kuki Gallmann and The Time Traveller’s Wife flooded my heart into a pool of sorrow, an unexplored territory of my grief at the loss of she who epitomized my childhood. I filled out my sorrow with more words than I can remember. I poetized the moments that we lived through together and fictionalized those that I wish we had experienced. I had never before been imbued with grief as I was after she was gone.

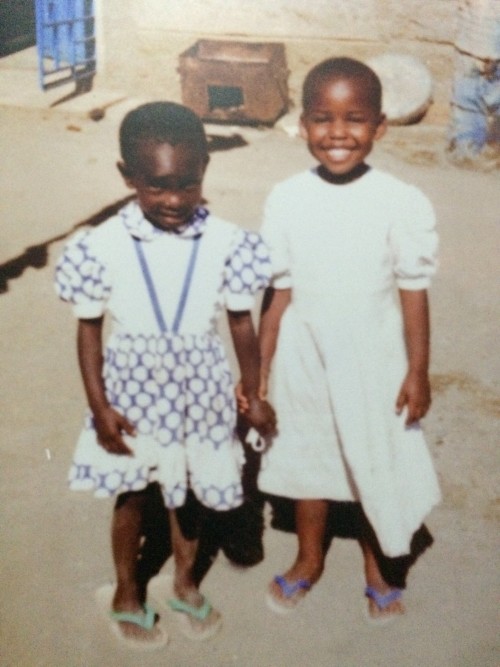

A few weeks ago, my mother gifted me with a blown up canvas portrait of that childhood. A lost photo from 1993, one whose details I have struggled to remember for eight years, the last time I think I saw it. I forced myself to stem the tears when I held our two-year-old likenesses in my hands, marveling at the clarity of the photo that had once lingered in the flaky edges of my memory. I could finally see my white dress with a navy skirt of white polka dots; finally trace the plainness of her white dress. We both have short hair. I have squinted my eyes, my head slightly lowered, while she, towering over me, smiles into the sun. I am holding what looks like a nailbrush, and she is holding my hand. The most curious detail is one that I have never forgotten – we are wearing each other’s slippers. I have on her green slippers that are too big for my feet. She has my blue slippers that barely fit her. I lingered at the image, wondering if in exchanging our slippers, we had exchanged our fates. I imagined how the portrait would one day find its hallowed place in my own home. How in my old age I would look upon her holding hand and remise how childhood begets the grief begets the muse.

Writing on the loss of my childhood follows a distinct pattern. It begins with her death, shifts to our childhood, and then ends in our celestial reunion. It has no adulthood. We were denied that. It begins and ends like this essay, like the classic trope of grief becoming all the more bearable because we imagine an afterlife with our loved ones. Writing is a never-ending journey. To think I have written the last words is to find myself resurrecting the familiar imagery months later.

Losing my childhood has stuck to my existence. I did not choose our friendship. I was born into it. And when you are born into something, you die with it. And you smile at the inchoate life that you once shared. And you cry into your adulthood because you did not know then that you would lose that limb; that child who towered over you and let you wear her slippers and held your hand. That friend you hope your theology will let you see when you are gone.

Check out Miriam’s blogs on her website. Get lost in her profound pieces on causes that actually matter and connect with her! She has a way with words, clearly, and is one of the most joyful, down-to-earth lady you will ever meet. This piece is a testament to that.

I knew a bit of her too 🙂 a life well lived.